The Flight Director: Role and Proper Use

- Fred Williams

- Jul 13, 2024

- 7 min read

Updated: Aug 9, 2025

In the intricate world of aviation, where precision and safety are paramount, the flight director stands as a critical tool for pilots. It serves as a bridge between raw instrument data and actionable guidance, helping aviators navigate complex flight scenarios with confidence. This article delves into what a flight director is, its components, its role in modern aviation, and how pilots can use it effectively to enhance flight safety and efficiency.

What is a Flight Director?

A flight director (FD) is an avionics system that provides pilots with visual cues to guide the aircraft along a desired flight path. It integrates data from various onboard systems—such as the autopilot, navigation instruments, and flight management systems (FMS)—to compute and display precise steering commands.

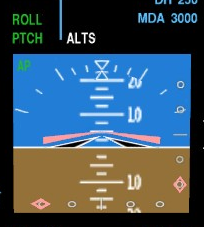

These commands are typically presented as crosshairs or command bars (v-bars) on the pilot’s primary flight display (PFD) or attitude director indicator (ADI).

The flight director does not physically control the aircraft (unless coupled with an autopilot). Instead, it acts as a "virtual co-pilot," offering real-time guidance on pitch and roll adjustments needed to follow a pre-programmed route, maintain altitude, track a navigation signal, or execute an approach. Think of it as a set of instructions that tell the pilot, “Fly this way to stay on course.”

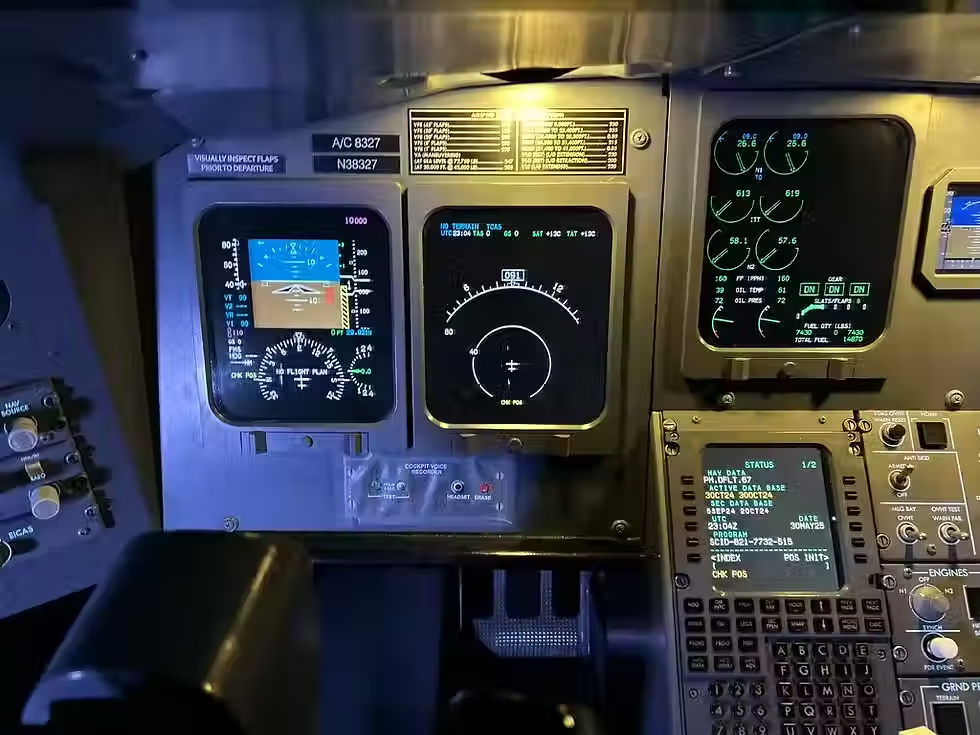

Flight directors are found in a wide range of aircraft, from advanced general aviation planes to large commercial airliners and military jets. They are particularly valuable in high-workload situations, such as instrument meteorological conditions (IMC), precision approaches, or complex departure and arrival procedures.

Components of a Flight Director System

A flight director system integrates several components to provide accurate guidance:

Flight Director Computer: The brain of the system, this processes inputs from navigation sources (e.g., GPS, VOR, ILS), air data computers (e.g., airspeed, altitude), and attitude sensors (e.g., gyroscopes or inertial reference systems). It calculates the required pitch and roll commands to achieve the desired flight path.

Primary Flight Display (PFD) or Attitude Director Indicator (ADI): The flight director’s commands are displayed as command bars or a single-cue “V-bar” on the PFD or ADI. These bars move to indicate the direction and magnitude of control inputs needed.

Mode Selector: Pilots interact with the flight director through a mode control panel (MCP) or flight guidance panel, where they select modes like heading hold, navigation tracking, altitude hold, or approach mode.

Navigation Sources: The flight director relies on inputs from navigation systems such as VOR, ILS (Instrument Landing System), GPS, or an FMS to define the desired flight path.

Autopilot (Optional): When coupled with an autopilot, the flight director’s commands are automatically executed by the aircraft’s control surfaces. In manual flight, the pilot follows the FD’s cues by hand-flying the aircraft.

How the Flight Director Works

The flight director continuously compares the aircraft’s current state (position, attitude, speed, etc.) with the desired flight path, as defined by the selected mode and navigation inputs. For example:

In heading mode, the flight director commands the pilot to turn left or right to maintain a selected heading.

In navigation mode, it guides the aircraft to intercept and track a VOR radial, GPS course, or localizer.

In approach mode, it provides precise pitch and roll cues to follow an ILS glideslope and localizer for landing.

In altitude hold mode, it directs pitch adjustments to maintain a specific altitude.

The command bars on the PFD move dynamically to indicate the required control inputs. For instance:

If the bars move upward, the pilot should pitch up.

If the bars move left, the pilot should bank left.

When the bars are centered, the aircraft is on the desired flight path.

The flight director simplifies complex tasks by reducing the pilot’s need to interpret raw instrument data. Instead of cross-referencing multiple instruments (e.g., attitude indicator, heading indicator, and navigation display), the pilot can focus on following the FD’s intuitive cues.

Proper Use of the Flight Director Using a flight director effectively requires a combination of technical understanding, situational awareness, and disciplined flying techniques. Below are key guidelines for its proper use:

Understand the Selected Mode The flight director operates in various modes, each tailored to a specific phase of flight. Pilots must confirm the active mode and understand its behavior. Common modes include:

HDG (Heading): Commands turns to maintain a selected heading.

NAV (Navigation): Tracks a navigation source like a VOR, GPS, or localizer.

APP (Approach): Guides the aircraft along an ILS or RNAV approach path.

V/S (Vertical Speed): Maintains a selected climb or descent rate.

ALT (Altitude Hold): Maintains a specific altitude.

FPA (Flight Path Angle): Guides the aircraft along a specific vertical trajectory.

Before engaging the flight director, verify the mode on the mode control panel and ensure it aligns with the intended flight task. Misinterpreting the mode can lead to incorrect flight path deviations.

Cross-Check with Raw Data While the flight director simplifies flying, pilots must avoid over-reliance. Always cross-check FD commands against raw instrument data (e.g., attitude indicator, navigation needles, or altimeter). For example, during an ILS approach, verify that the localizer and glideslope needles align with the FD’s commands. If discrepancies arise, revert to raw data to avoid following erroneous guidance.

Maintain Situational Awareness The flight director is a tool, not a substitute for situational awareness. Pilots must monitor the aircraft’s position, altitude, and trajectory relative to the flight plan. For instance, when tracking a VOR radial, ensure the aircraft is within the radial’s usable range and not drifting due to wind or navigation errors.

Couple with Autopilot (When Appropriate) In high-workload scenarios, such as flying in IMC or during a precision approach, coupling the flight director with the autopilot can reduce pilot workload. However, pilots must monitor the autopilot’s performance and be ready to disconnect it if the aircraft deviates from the desired path.

Use in Manual Flight When hand-flying, follow the flight director’s command bars smoothly and precisely. Avoid abrupt control inputs, as these can lead to oscillations or overshooting the desired path. For example, if the command bars indicate a slight pitch-up, gently pull back on the yoke rather than making a sharp correction.

Know When to Turn Off the Flight Director In some cases, the flight director may provide distracting or irrelevant cues. For example:

During visual flight conditions (VFR), pilots may prefer to fly by outside references rather than follow FD commands.

If the FD is providing incorrect guidance (e.g., due to a navigation source error), turn it off to avoid confusion.

In emergencies, such as an engine failure, prioritize basic attitude flying over FD cues.

To disable the flight director, use the mode control panel or a dedicated FD button. Ensure the PFD reverts to a basic attitude display for manual flying.

Train and Practice Effective use of the flight director requires training and familiarity. Pilots should practice using the FD in a simulator or during training flights to understand its behavior in different modes and scenarios. Proficiency with the flight director enhances confidence and reduces errors in real-world operations.

Follow Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) Airlines and flight departments often have specific SOPs for flight director use. These may dictate when to engage the FD, which modes to use during specific phases of flight, and how to handle failures. Adhere to these procedures to ensure consistency and safety.

Advantages of Using a Flight Director

The flight director offers several benefits that enhance flight safety and efficiency:

Reduced Workload: By consolidating navigation and flight path data into intuitive cues, the FD reduces the cognitive load on pilots, especially in IMC or complex procedures.

Improved Precision: The FD enables precise tracking of navigation paths, such as ILS approaches, leading to safer and more accurate landings.

Consistency: When coupled with an autopilot, the FD ensures consistent performance across different pilots and flight conditions.

Enhanced Situational Awareness: By simplifying flight path guidance, the FD allows pilots to focus on other critical tasks, such as monitoring weather or communicating with ATC.

Limitations and Cautions

While the flight director is a powerful tool, it has limitations that pilots must recognize:

Dependence on Navigation Sources: The FD’s accuracy depends on the reliability of underlying systems like GPS, ILS, or VOR. A faulty navigation source can lead to incorrect guidance.

Potential for Over-Reliance: Pilots may become overly focused on the FD’s command bars, neglecting other instruments or external cues.

Mode Confusion: Misinterpreting the active mode can lead to unintended flight path deviations. For example, engaging V/S mode instead of APP mode during an ILS approach could result in missing the glideslope.

System Failures: Like any avionics system, the flight director can malfunction. Pilots must be prepared to fly without it, using basic instrument skills.

Real-World Applications

To illustrate the flight director’s utility, consider these scenarios:

Precision ILS Approach: During a low-visibility ILS approach, the flight director provides precise pitch and roll commands to track the localizer and glideslope, enabling a safe landing.

Complex Departure Procedure: On a standard instrument departure (SID), the FD guides the pilot through a series of heading and altitude changes, ensuring compliance with the procedure.

High-Altitude Cruise: In navigation mode, the FD helps maintain a GPS or FMS-defined route, reducing pilot workload during long flights.

Conclusion

The flight director is an indispensable tool in modern aviation, bridging the gap between raw instrument data and actionable flight guidance. By providing intuitive pitch and roll cues, it enhances precision, reduces pilot workload, and improves safety in challenging flight conditions. However, effective use of the flight director requires a thorough understanding of its modes, disciplined cross-checking, and adherence to SOPs.Pilots must approach the flight director as a partner, not a crutch, maintaining situational awareness and basic flying skills to ensure safe operations. With proper training and disciplined use, the flight director becomes a powerful ally, guiding aircraft through the skies with unparalleled accuracy and reliability.

Whether you’re a student pilot learning to fly by instruments or a seasoned aviator navigating a busy terminal area, mastering the flight director is a key step toward safer and more efficient flying. So, the next time you see those command bars moving on your PFD, you’ll know exactly how to follow them—and when to trust your instincts instead.

Comments